172 notes to myself on art written while sitting on my bedroom floor facing my open closet in Toronto

Hello so this is something I wrote I’ve never been able to publish, for reasons that will probably become clear once you read it: it’s really long, it’s not any particular form, it’s very meandering, and perhaps above all, it was written mostly for myself—though you can tell there is some awareness of a potential audience throughout. In any case I’ve always liked it and it’s prominent within the category of “I would be sad if when I died this just got destroyed when my laptop gets thrown in the garbage without anyone having read it,” and since it’ll probably never get published any other way, I thought I’d throw it out here.

Most of it was written in 2014-2015, after I finished my MFA in Alabama and was living in a second-floor apartment on Queen Street West in Toronto across the street from the Parkdale Branch of the Toronto Public Library, above the Queen Fresh Market, which was run by a woman named Elaine, and her husband, who I never talked to. These notes are what I would work on after spending hours and hours and hours drafting novels that never seemed to cohere, and that also have never seen the light of day. When I started writing it, in the summer of 2014, my day job was selling bottles of Mill St. Organic at the Cirque du Soleil on Cherry Street next to my 17-year-old coworkers and making popcorn in a machine that looked like this:

I was 31. Later in 2014 I became a busboy, then a server, at the University Ave. Pizzeria Libretto, and by the end of 2015 I had started to teach writing at George Brown College. I revisited this document in a semi-major way a couple years ago, in an attempt to try to get it out into the world, but for this publication I resisted updating it too much and so am valuing its internal integrity as a ‘work’ over consistency with my current thoughts. Maybe I will just say though that the amount of control over one’s art that in 2015 I thought was desirable, or optimal—I now don’t believe anything like that is even remotely possible.

At points these notes are really self-referential/self-involved, i.e. I talk about my own work, pieces I’ve published, and even what friends had said about pieces I published; I guess I want to say that this is because these notes were me trying to make sense of my own work and why I do what I do. I don’t exactly know if it makes sense to publish them, then. But that’s what I’m doing.

172 notes to myself on art written while sitting on my bedroom floor facing my open closet in Toronto

1. A. recently wrote a thing and it’s so easy to see how important love is to making good work; she was so lonely and miserable for so long and didn’t really publish anything and now her being-in-love is written all over the piece. And I want more than anything, like everyone else who doesn’t have it, to be in love.

2. All you’re looking for is the security to not be so terrified all the time. And maybe money would fix that. But in my experience love is the solution to that problem.

3. No one really cares what you think. Therefore, don’t offer opinions. Entertain. Comfort. Help.

4. Allowing your art to be a little stupid frees you up to create actual beauty, because beauty is not found in chaos; beauty requires form, and form is stupid and embarrassing.

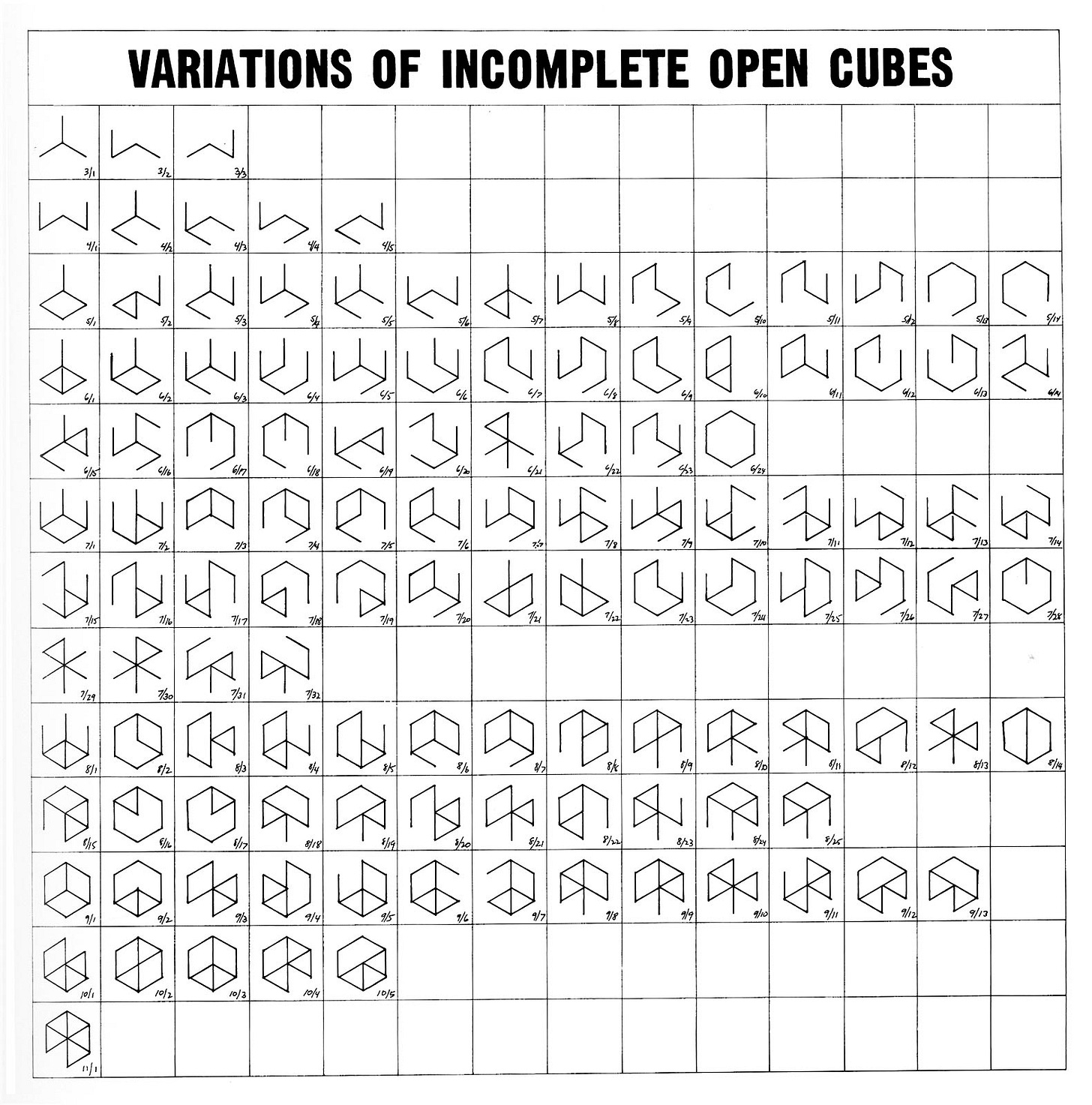

5. Sol LeWitt’s “Variations of Incomplete Open Cubes” (1974) is a good exemplar of ‘meticulousness for the sake of meticulousness’.

6. I probably think about this quote by Young Jean Lee more than any other: “Basically I try to think of the worst idea for a show I could possibly think of, like that last show in the world I would ever want to make. And then I force myself to make it.”

7. The Robert Ashley song “In Sara Mencken, Christ And Beethoven There Were Men And Women (1972)” is the best example of something whose premise seems unbearably pretentious and clunkily experimental but that actually works.

8. The bravest and hardest thing is to be humble enough to employ a recognizable trope; i.e., to participate in a tradition; i.e., to admit you’re human. (Cf. T. S. Eliot, “Tradition and the Individual Talent” (1919))

9. Aim lower. Be as lazy as possible so that all your energy is available for the one important thing. Your prime directive at this stage in your artistic career is to say no new projects and actively ignore new thoughts.

10. A piece of paper I had taped to my wall in Alabama said “Get stupider, worse taste, poorer taste, clumsy/broken, hi5.”

11. As always, cleaning = working. Best thoughts, freest thoughts, most easy associations and unconscious development come when cleaning. Or lying in bed waiting to go to sleep at night.

12. Theory/technique/how-to books are good to read once but art is made in response to art. If you’re not in conversation with other artists—if things other people are doing or have done in your medium aren’t fucking you up right now, at least occasionally—you will struggle with motivation.

13. At one point I thought: literary fiction is a graveyard and a mistake. This medium is a holocaust of egos, it’s uninteresting people cosplaying past heroes. In order to create something good within the ‘literary fiction’ realm, I have to work in that form but consider myself as embedded in a totally separate community—the realm of the real world, my actual friends, who are musicians and scientists and lawyers and midwives and flower sellers. The only way fiction has ever been good is by cheating the form, by airing out the mausoleum and bringing in trauma and condoms and tweets. By bridging the received form and contemporary life. While at the same time, in order to make actually good art, being a little nerdier than someone with avant-garde aspirations. The ideal artist is the nerd at the party.

14. And it’s not really that bad, or it’s just Sturgeon’s law, and periodically someone comes along and saves the form and then it feels exciting again, and we all remember why we love it so much.

15. And it’s never actually predictable. Part of the difficulty of fiction as a medium is there isn’t a constant supply of good books, it’s more of a black swan event when someone good appears: Lauren Oyler brings in the condoms and tweets, yes; but Sally Rooney, though she does that a little too, is more just doubling down on fundamentals.

16. If you quarantine yourself off into a ghetto for dead art you will be stupid and your thoughts will be limited and stupid.

17. All mini-worlds (subcultures) are echo chambers and statements made in them are invariably partially infected by people trying to impress each other. The game of snobbery that makes “seeming smart” (e.g. Didion’s famous Aug 16 1979 takedown of W. Allen in the New York Review of Books, and pre-epiphany Frances in Conversation With Friends) as important as “discovering truth” in writing-about-books poisons the whole enterprise. Not to mention the horseshit people will write when they’re getting paid.

18. It’s not merely difficult, it’s impossible to have a robust and highly-predictive understanding of the world if you exist in merely one meme stream/intellectual milieu. You need a more diverse sample size. Getting outside your normal discourse community is absolutely necessary to see the arbitrary (or status-mongering) rules of the game you’re in.

19. This is why I like the Twitter rationalists/postrats/EA/LW people. It’s just a totally different memeplex. The received wisdom, the common knowledge, is different, and it’s refreshing.

20. There’s no shame is switching mediums. (Cf. Fin in CBC: ‘rotating the crops’). Follow your ‘genius’, in both senses of the word (i.e. in Latin, ‘attendant spirit present from one’s birth’—a thing outside you; and the English). Follow your real interests. Follow where your energies and excitements actually live. If you have been doing art for a while there is a locus of energy inside you where your feelings are constantly recombining and expressing themselves in the language of your art. This is a fountain of energy that will keep producing as long as you are alive. You can make art that shoots up from that geyser or you can make art that comes from your spreadsheets. Guess which one will be good.

21. Of course, you want other people to feel it too, and so you’re always chasing the world, trying to feel the world’s feelings on behalf of itself. To be honest I don’t yet know how to synthesize these two imperatives. To nurse an inner geyser of the world’s feelings. To be its vessel. Of course the world in this sense is just other people.

22. It can get unpleasant, every time you realize something about yourself, if you want to publicize it, to roll it over and kick its red belly to make sure it’s acceptable to the public. But that is what you have to do if the group of people you care about includes people unlike yourself, and if you are only motivated to realize things about yourself if you can make them public.

23. You always have collaborators, even in ‘solitary’ arts like writing fiction. Your friend-readers and people whose opinions you ask and your editors are all your collaborators. Treat them as such and respect them as such and value them as such.

24. The best art is not-art; the best art is what you do when you give up on making art. The best art is a little more straightforwardly functional and has grown organically from a real need to communicate something, rather than a ‘statement’ you’re so arrogantly proud of. Tolstoy: ‘art is just an extension of regular human activities’ or ‘art is regular human activities done with particular care’. A novel is just a long speech act, a long story.

25. If you think you know what your art is going to mean and you don’t discover its meaning along the way, it will be bad.

26. One of the hardest lessons to learn is how profoundly you must pivot on the point of your art. You must make it the north star all endeavors of your life seek, yearly and hourly.

27. This seems unrealistic and ‘romantic’ until you meet someone who actually does this; then all of a sudden it becomes possible.

28. Of course it is still impossible and you can never do it. No one is that good.

29. But you can try.

30. But—— how much do you need your art?

31. Needing your art seems like a bad thing.

32. Needing your art is good in that it’ll keep you tied to it and you’ll keep doing it, but it’s bad because you can’t pull away from it and then lunge back in violently and abuse it, exploit it, make it do things it didn’t want to do, things it didn’t expect, things no one else had asked it to do, which seems to me how innovation happens, how interesting, urgent-feeling things happen.

33. Very strictly speaking, the ‘self’ is a fiction; or, put more neutrally, ‘the self/other dichotomy’ is something that refers to a real phenomenon but is also something that can safely be ignored when engaged in certain activities. Activities such as creating art, where, when things are going right, you will not care whether a particular idea or technique came from your own mind or someone else’s, and you will not care whether the work of art makes you (your civilian non-artist self) look good or bad. All the focus is on whether the art itself is good, which is another way of saying all the focus is on the experience of the audience or reader, not you.

34. To me the most profound point of integration between experience and art is in rendering faithfully and resonantly a well-known trope. To do so is to surrender, to submerge the ego in something greater than itself. The ego wants to be iconoclastic and ‘experimental’ and puts up a hell of a fight, but if you can allow yourself to commit the pedestrian sin of employing a recognizable trope, or somehow sneak a recognizable trope into your work by accident (then, upon seeing it, realize you like it, and feel reluctant to strike it), the reward of seeing something universally understandable drawn by your own hand, which then becomes not recognizably your hand at all but a vessel of culture, of humanity, is one of the sovereign experiences, I think, of being alive. (This is the phenomenology of “Tradition and the Individual Talent.”)

35. A trope is a feeling—sometimes. It’s trying to be anyway. If it’s executed with sufficient subtlety and camouflage. If it’s made to resonate, to sing, which is a matter of knowing your audience and the notes they bend to.

36. To be able to manipulate emotions—what power.

37. The tragedy of art expertise is this, though: when you’re at a point where you’re so familiar with a trope that it becomes second nature and you can employ it on the fly, naturally, offhand, whenever your mud (cf. Trecartin @ The Drake Hotel, March 2010: “mud” as subconscious art-processing plant) sees fit, the trope has completely lost its emotional power for you. And so you become progressively inured to the power of art even as you become its master.

38. A masterpiece, then, is easy to make—for the master. It’s equally as rote and equally as inspired as any other piece of art he or she has ever done; they’ve just been doing this for a while. (Picasso: dashes off a drawing for a stranger and says “one million dollars” and the stranger says “it only took you five seconds” and Picasso says “it took me forty years.”) (This is the coolly stated version of my outburst when DFW died, that he couldn’t be comforted by his own work.)

39. There’s something about the floor and reading and writing, something about being low to the ground. I feel scattered and confused until I clear the floor and sit. It also helps if I sit facing my open closet. It humbles me. There’s something deathlike about it in that it opens onto nothing but it also feels most ‘transcendentally’ like life: the shoes, the shirts, the umbrella, the instruments of one’s existence.

40. Every single work of art has an implied location, an implied heartrate, an implied physical posture, and an implied relation to other people. Also an implied set of sexual/relationship mores, an implied income, an implied attitude toward food and travel and TV and the internet, an implied tax code the artist is living under.

41. Heartrates: Anne Carson, “The Glass Essay”: 100 bpm. Kate Beaton, 70 bpm. Daredevil (TV show): 40 bpm. When you’re at your peak, capable of scaling a cliff’s edge, you can do Carson. When you’re half-dead, you can do Daredevil. Kate Beaton is something like the achievable median.

42. The heat of a work of art is in its attitude, not its content. That’s why you can usually cut almost everything and the feeling of the artwork will remain, if it has any feeling to begin with.

43. A work of art, unlike almost everything else, is about ONLY ONE FEELING. (Often however a pretty complex feeling which won’t have a name, and the artwork or artist becomes shorthand for that feeling—Lynchian, Kafkaesque the most extreme examples, but there’s a long tail of almost every other reasonably distinctive and consistent artist that don’t get memeified like that.) In a play or movie, you can build to that feeling, but in prose, every sentence is an instance of that feeling. That’s why syntax is the primary vehicle of prose art. The syntax expresses the feeling of the speaker, no matter the word choice.

44. Not to belabor it, but every artwork implies an entire lifestyle; and it’s going to be the one you the artist are living, so it’s time to give up trying to fake otherwise. A potboiler about a black gumshoe in Washington, D.C. is, because of the way it’s written, actually about the experience of being a married middle-aged white man in Florida who writes for money (Patterson). (In the same way that the contours of a comedic sensibility describe the pain it comes from.)

45. Nothing, including writing about art, feels as good as doing art. You really feel the truth of this just after you actually do it (make art). What I’m doing now is like warm-down stretches.

46. Life provides the content, other people’s art provides the form, sleep and cardio and drugs and free time and spending time with friends provide the energy.

47. One of the many reasons why being ‘insincere’ is necessary to create good art (cf. Wilde, Nabokov, Eliot) is because once you have internalized a trope to the point where you can employ it at the drop of a hat, it feels to you fake and insincere. But if you maintain your precious allergy to something that feels easy and understandable, you’ll never allow yourself to employ this trope which despite being pure math to you now, once meant so much to you, and still has power for others who don’t spend all day every day making and/or dissecting art.

48. This list is easy for me to write. I have mixed feelings about that.

49. It’s interesting to me how making everything else in one’s life pivot around one’s art can take on different forms. Until recently, for example, it hadn’t occurred to me that consideration of my art career would have bearing on my choice of who to be in a relationship with. Now I think about that.

50. This is a change from five years ago, when I wrote that I had “given up trying to be happy and replaced it with trying to make good art.” At that time, the primary concern was the artwork itself. Now it’s more the career, or the way of life, perhaps because I’ve settled many (though far from all) of my artistic problems and I recognize that mostly what I need is time and energy and concentration and money, and so it’s mostly the material circumstances of my daily life that shape what kind of art I will make, as opposed to me trying to mimic others’ work I’ve loved (as in my past). I’m always worried I’m going to fall into some kind of life where it’s very difficult for me to create art, and so I find my vigilance focusing on protecting my time, and thus my lifestyle. This is I guess Neil Gaiman’s ‘mountain’ strategy: eyes always on how to create a practicable and sustainable life of artmaking, not on how to make art, which at this point is largely—though, again, certainly not entirely—assumed knowledge.

51. Of course, everything can be overdone. If you have no feelings but “wanting to succeed,” your art will starve. It needs to feed on your civilian life. Your emotions that run deeper than ambition, which you sometimes forget exist.

52. Maybe especially in prose, the form is the content, and the best content is always the most heartbreaking, when the writer has given the work everything they have and it still doesn’t resemble something that has come before, because the artist is too pure and stupid and uncompromising and true to themselves, and in their failure to be perfect you see what a human is and that is art.

53. In its purest manifestations the form conforms to the life lived. Montaigne’s friend dies and he writes on every random topic and so shows us himself and his loss. Munro has no time for a sustained narrative between raising children and so shows us what it means to live that life. Lin’s dashed-off essays express his priorities.

54. Corollarily, every moment of an artist’s life is performance, because he or she must know that their life will be ‘read’ as the paratext to help explain their work. Insofar as they can control events in their life, they can shape the meaning of their work. Insofar as they cannot shape events in their life, the control of their work is imperfect and again we are shown what it is to be human, against the artist’s will, who would rather us think them the total master, above determinism, certainly not subject to some off-the-shelf ‘identity’.

55. The more we love the artist the more epic seem their flaws and the more significance we read into the identifying features of their lives. But in fact the world is suffused with wife-beaters, alcoholics, people who die getting alternative treatment for breast cancer in Mexico, and so on. But with unknown civilians we read into their actions the most Occam’s-Razor-y motivations, whereas with artists—especially, perhaps, when we’re young—these biographical factoids overwhelm us with their significance.

56. I’ve been thinking about the idea that “to succeed you have to give up” since I wrote a philosophy essay in high school on it and quoted Nietzsche and that Aimee Mann song from the Magnolia soundtrack. I never understood the idea, even though I pretended to when I wrote my high school essay. (I’ve also never understood “you always kill the one you love,” which seems wrong to me.) But I feel like with my recent adoption of the dictum to exclude all ‘art’ from my art, I may be close to understanding it. For example, in my Facebook posts I’m not ‘trying’ at all, and that, I think, is some of my best work.

57. ‘No art in art’: fiction is just the art of telling a story the best and most effective way you can figure out; nothing more, nothing less. Performance art is just trying to communicate an idea or feeling with your body. 2D and 3D art, same, with their respective media. Allow yourself to let the ‘tradition’ and what everyone else is doing fall away. When you are actually in the moment of creation, you are not part of a ‘conversation’ with your tradition or your peers, except insofar as biting canonical techniques helps you to communicate with your audience. It’s just you and your reader in a room; of course to be alive is to know there’s a whole world out there, somewhere; but we’d like to try to forget that as much as we can while we’re together. Don’t raise your voice artificially so that the headmaster passing in the hall may be impressed by your vocabulary. It’s just us, here. Let’s make the most of our time in this room. (I suppose this is related to my “Songs From Another World” (2012).)

58. I’ve found, very much accidentally, that the most valuable resource for my being-able-to-write is ‘not feeling like shit’. I used to upbraid myself incessantly and almost passionately for my shortcomings, and so many things related to writing triggered this. Mostly I would compare myself unfavorably to other writers, and I would berate myself for copying their styles. But now this rarely happens. I’m not sure exactly why this is so except I started reading (via editing) my own writing more than any other writer’s writing (and so I think I copy myself more than any other writer), and also I’m in a place now where I find it easy to publish, and also I moved back to Toronto and am happy here.

59. Everyone has big feelings; that’s not what makes a good artist (Haruki Murakami, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running). It’s the effort put in.

60. ‘Branding’ is a concept that’s now ubiquitous in literature meme streams, but something I’ve never heard non-journo writers talk about is having a ‘beat’, i.e. committing yourself to covering certain thematic ground so that you can become an expert in that and become known for that. I picked this up in my journo class at Alabama and feel lucky to have done so. It allows me a way of making sense of committing to certain constants, e.g., to writers and artists as protagonists, to a certain sensibility. (I probably—certainly—don’t accord enough power to ‘because I feel like’ as a reason for doing things. I’m always tabulating.)

61. Ariana Grande’s knee-high boots: she keeps one item constant for brand management and this allows any (sartorial) thematic explorations she does to still ‘feel like her’. Some obvious examples of this are like Wes Anderson, David Markson, Jeannette Winterson, Mary Gaitskill.

62. I never read any Steinbeck at all until the last few weeks when I read Of Mice and Men and a little Grapes of Wrath. I liked Mice and Men but when I got to the end of the opening section of Grapes I realized that Steinbeck is a sentimental tale-teller and I compared him to Hemingway in whose best novel, Sun, there’s full commitment to ‘no magic, no falseeasy conclusions’. Now this is a going dichotomy in my mind.

63. Two people exit a story living ‘happily ever after’ in the same completely arbitrary and formal way that the angels enter “The Entombment of Christ” via the upper corners of the painting: the angels are coming into the artwork from the corners of the rectangle (arbitrary frame of the work) as the two people’s relationship stops at the end of the last sentence or after 90 minutes (arbitrary frame of the work).

64. Making very good art is exactly coextensive with destroying pieces of quite-good art, and that’s why making very good art is so difficult. Because of humans’ loss-avoidance instinct, which is stronger than our drive to acquire, even when you create something truly beautiful—that for which you sacrificed your ‘babies’—the tragedy of that murder is so powerful it can overwhelm the joy of the final accomplishment and leave you unable to see the beauty of what you’ve actually managed to do. Jonah Hill’s character showing Brad Pitt’s character the video reel of his unacknowledged (by him) accomplishments at the end of Moneyball.

65. To think that you can choose to be an artist other than yourself is pure fantasy (cf. John Currin: “Your style is who you are when you’re not trying to be clever or better than you actually are.”) I used to think, like, “shall I be a writer like Bret Easton Ellis or Iris Murdoch?” And I still catch myself imagining I could be someone I’m not. But how laughable this is comes into focus when you hear someone else analyze your work. One time at Bellwoods Brewery, Sasha was analyzing what he understandably took to be the “choices” I made in “The Life You Want,” and he was comparing my juxtaposition of everyday banalities with melodramatic clichéd language to Beckett, and saying it was a smart move for our time. It made me think of the original title of my “Songs of Another World” essay, “All Your Heroes Are Lazy Dumbasses.” Because I’m just not that smart or virtuosic. Those decisions are just me talking, that’s how I talk. The three names in that story are just the names of my real friends I’d seen that day. A year or so later, when Catherine wrote about “The Life You Want” in Sludge Utopia, saying she disapproved of performing despair in literature, I had the same thought: you think that’s a performance??

66. On the same note, you can’t choose what works well for you (as an artist I mean, but also in life); you can only experiment. Trial and error.

67. You will of course have hunches.

68. There are (at least) two ways of “being yourself” (both as an artist and as a person). There is the way where you force yourself to be yourself, i.e. to vigilantly avoid being other people and using their memes (their turns of phrase, their life decisions (smoking, going to grad school, being in a committed relationship)), and then there is the way where you’re a little more relaxed and you allow yourself to use whatever memes come naturally to you, feel right to you, irrespective of provenance, and those memes become who you are, even if they’ve also been important to other people, or your images of other people. E.g. the decision to ‘become a punk’. Sophia Katz has a good poem about this. I feel like these two approaches basically map to ‘the younger sibling’ and ‘the older sibling’.

69. A more secure person feels more comfortable with the latter, because they don’t need to be unique to be free or respected. An insecure person for whom being culturally elite is their only form of power needs very much to be unique. Hence the insecure personality of the socially-outcast teenage art snob.

70. This is also perhaps the difference between an artist’s early period and later period, or a certain kind of person’s early personality (obsessively controlled, devoted to rigid precepts) and their later personality (in conversation with the world, responding to others). Wittgenstein obviously the paradigmatic example.

71. To go back to “excise all the art from art”—obviously this is something you do after apprenticing for a very long time, when the tropes and techniques are no longer baffling instruments but rather extensions of your limbs, like fingers you can control without needing to think about. Then it makes sense to say “eschew what does not feel natural.” A baby can not eschew all art.

72. I’m realizing as I write that my recent decision to “choose the easiest structure possible,” because of my struggles with structure, is related to the above. Now that I’ve written 200 stories and 2000 daily entries and 2000 Facebook posts and read craft books and had a million conversations about art and writing and some of my most successful work is in weird uncategorizable forms, it sort of makes sense that I would think “fuck structure.” My subconscious has internalized enough structure; I don’t need my conscious mind meddling with it.

73. I’m not interested in fiction that isn’t on some level commenting on the form itself; that isn’t in some sense a metafictional manifesto delivered in the form of fiction. I suppose this is the artistic version of Kant’s “act only in accordance with that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it become a universal law.” In any case I’m always thinking about the phrase “metafictional manifesti.”

74. No fiction in which it’s not basically quite clear that actual notes have been taken from actual life will ever make my pulse quicken.

75. However, what a novel like Eat When You Feel Sad doesn’t get, or want to accept or deal with the reality of, is that art is at least as hard as life, and the artist in creating the art must make at least as many decisions as the artist living the life on which the notes are taken.

76. This is because reality is extremely repetitive and redundant, but art must not be.

77. Every particle of an artwork must mean. (Barthes has a great analysis of Flaubert’s description of a bunch of objects on top of a piano, explaining that the description’s superfluity itself makes the scene feel real, which sounds prima facie like a bit of a reach but I actually agree with it and it’s probably the most purely ‘theoretical’ craft idea I actually use.)

78. The whole challenge, though, is in concealing the function. “We’re just taking a walk, sniffing the autumn leaves. The fact that I’m going to accidentally reveal to my son that I’ve killed his mother must not seem like the ONLY reason for this scene to exist. We must get much more from this scene.”

79. Compression is the absolute king of prose, because, of all the artforms, prose demands the most energy from the human body, and therefore whatever can be done to increase the emotional/informational throughput per alphanumeric character is our goal. (Lots of people parrot “omit needless words,” but they don’t understand why. It’s because of this.)

80. This is why although ‘notes from reality’ are necessary, one must start with tropes, as opposed to being motivated by “something interesting or weird or moving that happened.” Tropes are information, tropes are tied directly to human biology—e.g. think of the primacy to human experience of a nostos or an aubade. There’s a reason homecomings and lover-leavings became represented so much that they got their own name. “Something interesting or weird or moving that happened” is just ‘news of the weird’.

81. This instinct leads me to feel that novel-writing is barely art at all. It’s almost pure engineering. You can’t have feelings about basically any aspect of it or the whole edifice will tumble sidelong into the abyss and you will be left alone with the bare-branch-sticking-out-the-side-of-the-cliff of your own uselessness.

82. However, my repeated failure to write any novels probably means this is totally wrong. And lately I’ve had this intution that writing a good novel is like building a house on a swamp. A bad novel you can write anywhere. You know how you want it to look and you start building and that’s how it comes out. You haven’t discovered anything, and it’s in a boring location. For a good interesting novel you need to home in on interesting mysterious territory that you don't really understand—a swamp. You start building, but you have to go deep into the messy sludgy underwater parts of the swamp to figure out how to even build the foundations. And only when you understand the contours of the deep can you even start to build your structure, which will be fundamentally shaped by what you discover in the deep.

83. In our era, certainty is a product.

84. I wonder if this has contributed to my problems. Certainty is both extremely in demand and extremely easy to manufacture. In this way it is like high-fructose corn syrup.

85. But unlike HFCS, it’s not labeled as such, and so it can be difficult to remind yourself as you’re scrolling, e.g., Twitter, that all this is distilled, artificial certainty. People disingenuously maximizing their certainty because they’re rewarded for it. (One of the most enduring lessons from a cognitive science degree was decoupling “feeling of knowing” from knowing.)

86. For the careerist, I suppose there’s no debate. You should take advantage of this. Become a con artist, sell fake certainty via ‘message-driven’ art, especially since this is 100x likelier to land you a career. It’s possible the temptation is so great to do this that eventually anyone who’s able to drifts into that path.

87. But for the artist (insofar as there’s daylight between artist and careerist), I think you should resist this as long as you can, because by doing so you cut yourself off from your illegible confusion, which contains so much more than your reason and is so much smarter than you are. There are more things in heaven and Earth, Horatio, / Than are dreamt of in your philosophy, and so on. Or at the very least, you need to maintain an artist who’s a deep sea diver, in addition to any con artist editor you accumulate.

88. “If you think you know what your art is going to mean and you don’t discover its meaning along the way, it will be bad.” Is this true? I don’t know. After The Jokes was published I remember telling A. how I never expected to write a story like “Presidential graves,” about the like weird amoral vanity of children; that’s just what happened to come out in the editing. However, that story is only 142 words long. It seems at least probable that the ability of a draft to completely change its meaning simply becomes unworkable above a certain word count. I can’t say I know.

89. Maybe, above all, you cannot really choose: the writing of a novel is the incentivizing of a mouse along a maze contained within a glass cube. The maze is your outline, which you create in good faith (or not; perhaps you create it with commercial instincts in mind), but you cannot directly touch the mouse, which is the narrating consciousness that speaks the book. You cannot force the mouse to go in the direction you want it to; you cannot force the mouse to do anything. Ultimately the mouse writes the book. You simply give it options, and provide it the raw materials, feed it, keep it happy, and well-slept.

90. The truth is I have no idea how to do it, any of it.

91. But I’m trying.

92. If you don’t feel like a failure at the end of the day it means you haven’t tried.

93. FWIW, the thing that finally enabled me to write about the hardest time in my life (when my family imploded and I dropped out of university) was getting a job (busboy) that completely exhausted me three or four days a week and in general left me with less energy to think about things too much. In this exhausted state I basically felt like, ‘what’s something I’ve ever cared about, what makes me feel anything?’ instead of living in neuralgic fear of triggering a flood of painful memory-emotions, which had been my default state for a lot of the previous years.

94. I am at a stage of development. I am not an expert. I can do some things, but not others. If I try to do things I can’t do, I will fail, and I will be unendingly frustrated. It often feels like my development has in many ways (artistic & life) reached completion, but that is wrong. I will be able to do more things in the future. Right now I can’t do them. So right now I should do other things. More modest things.

95. As time passes, what seemed like a wildly ambitious project becomes a modest project. Eight years ago it wouldn’t have made sense for me to say “I’ll just write a short simple novel.” But now that seems very reasonable, and I am in the process of doing so. The flip side is that now it seems beneath me. But it’s not, I haven’t done it yet—that’s exactly where my skill level is at, having completed several long short stories. Be modest enough to be at your own skill level, even if it’s not where you want to be.

96. In the early morning hours of August 13th 2015 I talked with A. on Google Hangouts and she asked me if I was feeling good, and I said yes, and I asked her if she was feeling good, and she said no. She was not happy about how her work was going. Her efforts were not achieving the intended result. I said mine weren’t either but I’d been thinking that between here and the future time when my efforts were achieving the intended result—where I’m making the good stuff—the only possible intermediary steps involve me making bad stuff. There’s literally no other path. It’s either do nothing and get nowhere, or make bad stuff and maybe, eventually, make good stuff. She said she thought I had a good attitude about this stuff.

97. It’s interesting to think that probably almost every shitty artist thinks that in some way they’re better than every good artist.

98. I don’t know, maybe that’s not true.

99. My “me” seems to be changing from artist/feeler/theorizer to provider, life-planner. Because I find my life falling apart so completely, becoming so random and chaotic, that I am finally feeling the need to take action on my own behalf, become a better manager of my own energies and days.

100. Skyping with A. on August 23, 2015, she asked me what I thought the feeling of writing well felt like and I said it was like the feeling of a word being on the tip of your tongue except you’re actually finding it, over and over again, and even though you can feel that you’re making a lot of little micro-decisions in the moment, with each word and phrase, you’re also in a state of constant surprise, you have no idea what you’re gonna say next, you’re just following the thread.

101. And in life perhaps that thread is love.

102. No art without love.

103. Love is this thing that makes you stronger by changing what “you” is and joining it with something beyond yourself.

104. Love is the thing that triggers a healthy dismantling of the self.

105. And you don’t feel limited, you feel released. From your own petty circumference.

106. Love is the thing that opens you up, that saves you from the version of your self that is more selfish than you wish to be, and more stuck.

107. There is an artist in me who is driven by love, and that is the good artist.

108. There is a person in me who is driven by love, which for me is not much more complicated than focusing on experiences in which I do not feel differentiated from the world. When I am not against the world, but acting as a part of the whole (Haidt’s bee-mind).

109. There is a shitty artist in me who is driven by ego. That is the childish part of me that is alone with my thoughts and gets disconnected from other people and is mad at not getting attention and tries to coerce affection from an audience by being flashy. But as in life no one ever owes you anything and your task is only to give.

110. Mostly to give.

111. Impulses that art satisfies: mimesis, catharsis, and discovery of the truth. Alt lit/mumblecore privileged mimesis. This is why the final line of New Tab felt so right. Catharsis is privileged by most mainstream narrative art, especially drama and tragedy. Discovery of the truth is what suspense and mystery are founded on.

112. It is often said that combining genres makes good art. But it’s more complicated than that. There is a right and a wrong way to combine genres. The wrong way is to do is haphazardly, such that the impulses compete with each other and water each other down. The right way to do it is to nest one inside another. Good examples of this are: Funny People, which is a Drama nested inside a Rom Com nested inside a Buddy Comedy. The structure is ultimately a buddy comedy, but scenes and tropes of Drama and Rom Com aide the plot development, and give it emotional texture. Another good example is The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, which, even though it mostly presents as a Mystery, is technically a Coming of Age story, as evidenced by the ending. And when you see it as a Coming of Age story, you see that although the Mystery architecture supplied the logical connections between the scenes, the Coming of Age story supplied the emotional justification for the tone and content of many of the scenes.

113. Finish projects. You can’t choose whether you finish something well, but you can always choose to finish it. My 77-year-old dad keeps working on songs and never putting them on YouTube, but he could just choose to put up what he has, and I wish he would.

114. So much of becoming a good artist is being thick-skinned enough to be a bad artist.

115. If you don’t finish a project, you’ll never get to be embarrassed by how bad it was, and so be motivated to do better. An unfinished project is always at least potentially good, and so is as useless as an unworn shirt that might look good on you, or a version of you that’s not quite you. But you are no one but you, right now. This is what you have to work with.

116. Remember to spend life, don’t save it. (Koestenbaum: “Utilize your youthful sexiness before it runs dry.”)

117. I probably put too much emphasis on “engineering art.” Not sure that’s possible. Have to use energy and impulses where and when they come. My critical faculty at this particular point in my life more highly developed than my generative faculty, which was tremendous age 18-24, but the material of which I had no idea how to shape. So now I have to jump on my creative impulses when they happen.

118. One of the most important lessons I ever figured out was, if I get an idea for a story, to drop whatever I’m doing and write it right then, for as long as the feeling holds. For me, about 90%, maybe 95%, of these times are as I’m lying in bed waiting to fall asleep. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the majority of the deep insights come during this window.

119. Art is 100% about feeling.

120. And it is 100% about the idea behind it.

121. Good art is the perfect union of a clear feeling and a clear idea. This may sound academic or trivial, but all it means is that good art is a perfect record of when something means something to somebody. If it means something to somebody, the feeling will be clear, and the idea will be clear. When a person says “Get out!” in anger—the emotion is clear, and the idea is clear. Art is exactly that but with slightly more complicated ideas, and usually but not necessarily more complicated emotions.

122. I’m scared. I’m scared I’m not good enough. I’m scared I don’t understand myself well enough to make good art. I’m scared I’m too confused and needy and my life is too chaotic and I’m too sad all the time to make coherent art. I’m scared I’m not disciplined enough. I’m scared I’m too shy and bad with people and scared that they don’t like me to be an ‘operator’ in the way that seems to be necessary to have an art career. I’m scared I have nothing to say and there’s no one who wants to hear it.

123. I’m scared I haven’t figured out a way to “forget my personal tragedy” in my life so far, and that increasingly my personal tragedy is closing in on me, rather than me becoming more liberated from it, as I’d hoped.

124. I’m worried that I’m losing motivation and relevance.

125. But an equally real part of me is convinced by some evidence that shows that not to be true. I try to be as dispassionate as possible when figuring out what I can offer people. The evidence suggests, at least sometimes, that people like what I do. It seems like I have things to offer people in the form of art, and that’s what I want to do. So I will keep doing that until it seems like I don’t have things to offer.

126. If you have a problem, others have that problem, and it is beneficial to them for you to express it, both so they can understand it better (if it’s well expressed) and so they can see they’re not alone. This is the art idea of my own that I come back to most often.

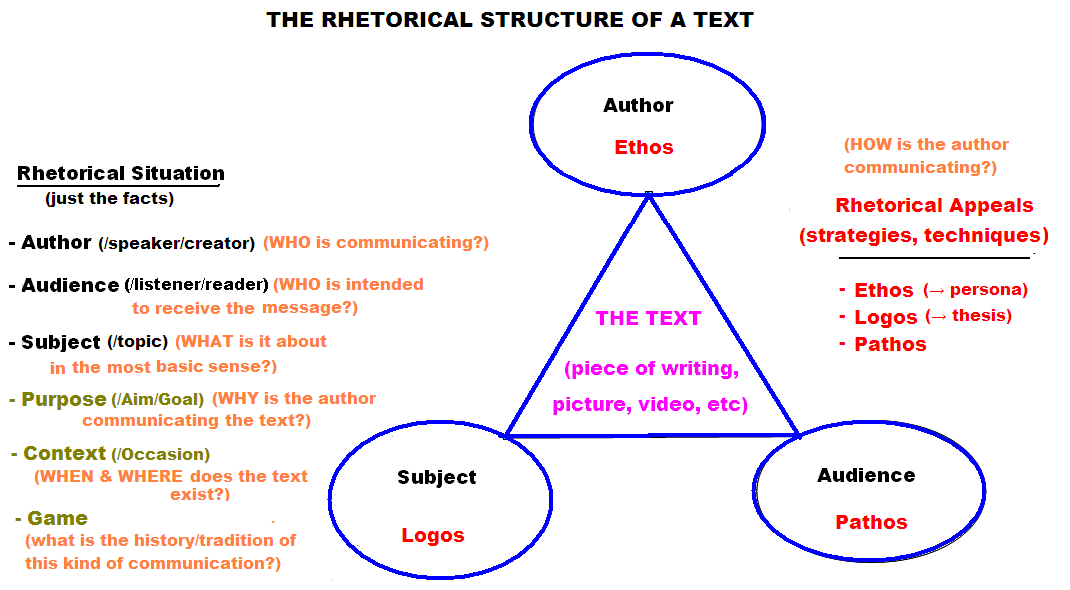

127. If you have a problem, others have that problem. The universality of human problems is your mandate to create art.

128. And for this reason the parts of you that are typical are more important to your art than the parts of you that are exceptional.

129. You need at least one person who is interested in what you’re saying. Kurt Vonnegut’s “Write to please just one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia.”

130. As I said earlier, a writer’s life is perforce performance art, because the writer’s life is always read as paratext to their work. Of course no one can control every aspect of their lives, but you do have a say. However, paradoxically, in order to get any good work done and not live in terror, I believe one must strictly not give a fuck about what any stranger thinks of you or your work. You are not everyone’s friend, you are not everyone’s ally. You are the friend and ally of those who feel you.

131. If the only thing you have going for you as an artist is that you’re young, you are going to have to figure out some other angles.

132. Here is a diagram I made:

The deceptively terrifying thing about this diagram is that “The text” is the only static thing—and then just barely so, contingently so. Everything else is an aspect of the real, changing world. This isn’t such a problem for a political speech designed for a single day at a specific hour, but for a longer work, the enterprise of engineering a stable context, a stable speaker, a stable purpose, and so on, is an immensely challenging undertaking. Imagine what it really means for a person in the real world to engineer a “stable speaker” that lasts for weeks, months, years. It’s hard. It can take up all the energy and all the planning and all the discipline. The cultivation of a stable context can become that around which an entire life pivots.

133. When you are in this zone, the opposite of childhoodness obtains: nothing interesting can happen (in your mind, your art) without an extremely repetitive lifestyle. Unpredictability is chaos and any elements of chaos except those pre-approved minor variations like what sonata CBC Radio 2 plays in the morning at 10 a.m. are counterproductive. They fuck up the laboratory; they introduce alien variables and make it so you can’t go back to where you were the day before.

134. The only history worth exploring is the history of times people have behaved in ways exactly like you behave: not more honorable, which is fake epic, and not less honorable, which is fake comedy (Aristotle). The only problem is that this history has never been written and you are the only person who can write it.

135. The above though is a too-perfect thought. Real art can never be that perfect. You have to hitch your wagon to forms you didn’t think of that you only half-understand and grind your soul into them and hope something beautiful will fall out. A human isn’t strong or smart or lucky enough to discover a new artform. Always a part of it is accident and strange impulse. Mary Shelley writing Frankenstein on a bet. Commissions, solicitations, occasional writing, improvisations. Collaborations.

136. Or the history of times people have felt the way you’ve felt.

137. Easing up on the Schiele and tipping in some Adam Sandler is exactly who I am. Remembering that in my best moments my heart doesn’t bleed. Thackeray, Heller, Vonnegut, Chris (Simpsons artist), Megan Amram.

138. Last night (10/11/14) I told Sasha my idea that a “local artist” isn’t a level, but a species. He liked it a lot and slammed the table, laughing, at the Communist’s Daughter. I said how it’s not like you start out as a local artist and graduate to an international artist. A local artist and an international artist have different goals, different audiences in mind, different ethics, different allegiances. But I didn’t really need to explain any of it after the first sentence, because he understood.

139. Naomi quoted me in her long piece on Richard Maxwell, where I said I feel vampiric being a writer sometimes, using other people’s lives, but later she told me she didn’t feel the same way and in fact didn’t really know what I meant by that. But that was before “A New Place” was published.

140. I had a beer with Evan Webber a few nights ago (11/25/14), and we talked about the thing of ‘using’ ‘material’ from the lives of people you know. Evan said it’s funny how it feels like a super important issue but at the same time the most boring one, like, “haven’t we figured this out yet?” But advances are being made. Sheila Heti’s book takes that issue as a central one, and the process of Jon and Amy’s Bugs movie, by getting their friends to improvise and create some of the content, also does (or will, I think, when it’s done). Evan also said “I think ultimately people are flattered to be thought of.” That feels pretty right to me. Darrah Teitel wrote a play where she put things I said in Lord Byron’s mouth, without running it by me, and though I felt a little mad, I also recognized I would never cast myself as Byron, and mostly what I felt was pride.

141. A couple days ago (10/21/14) I told Dan that because an event used the word “implicate” in its event description, I didn’t think it would be a good use of my time because the person who wrote it, who would also be the main speaker, hadn’t digested the ideas they’d received from school enough. He said “Does everything need to be dumbed down? Not everything can be explained to a five year old.” I said I think it can.

142. Jon McCurley is the best artist I know. I am really grateful I lived with him for three years. I learned a lot from him.

143. I’m so happy I found people to love after the horror show of my early twenties. It feels like I’ll love these people forever: Jon, Naomi, Sasha. I may have met them too late (mid-twenties) for us to be seared into each other’s brains in the same way as the people from earlier in my life, but maybe that’s better; maybe that’s how I like it. Maybe I like a certain distance.

144. The site of the majority of this piece of writing has been my bedroom floor, usually during or just after I’d done abdominal exercises.

145. “Good” and “evil” are properties of a narrative framework, not the world. The protagonist is good, the antagonist is evil. That sentence defines ‘good’ and ‘evil’ as much as it defines ‘protagonist’ and ‘antagonist’. Elaine Pagel’s tracing of various pre-Christian religions’ use of ‘Satan’ as a character/rhetorical maneuver.

146. You don’t work on the same novel every day. Every night you completely give up, and every morning you think “I want to finish a novel. What is the shortest route to that point?” And the answer is to do one day’s work on the novel-in-progress that happens to be on your hard drive. Or at least that has been my method so far which so far has totally not worked.

147. The accomplishment of a work is attributable equally to the practitioner and to the tradition, i.e., all the other people who had done similar things, which the practitioner’s work is biting. There is actually a substantive, not just metaphysical point to accepting that free will is fake, and this is it.

148. Therefore, be humble, be part of a tradition, use the tools others worked their whole lives to develop. “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” Stand on the shoulders of giants. Save the stupid little cat.

149. I no longer have any idea how to think about life separate from my goal of being good at art. A general contractor, a social worker, a flower shop cashier probably undergo similar experiences. The structures of your vocation become the metaphors of your thinking.

150. How to be good at art? It’s tempting to take the advice implicit in Seinfeld’s comment in the documentary about him when he says “the only people who become good comedians are those who can’t do anything else”—to take that advice and execute some kind of Ulysses contract with yourself to prevent yourself from dabbling in other kinds of art. However, every time I’ve dabbled in non-fiction arts, I’ve benefited enormously. Taking a poetry class in grad school, reading a How To Write A Screenplay book, writing a (joke) screenplay for a performance art show, taking a journalism class, writing journalism, writing experimental lyric-essay-type stuff, doing standup comedy, and probably above all, writing constantly on Facebook, have all only served to improve my fiction.

151. And it’s tempting to look at people like Seinfeld, who only ever did one thing (though not really; writing a sitcom script requires a lot of skills that stand-up doesn’t) and say: I see, someone who’s really good at something must have become good at that by only doing that one thing. But I think that’s a self-fulfilling myth that a lot of people believe which maybe results in it being true—all the young ambitious experts are too scared of being shitty to dabble, because it may have an aura of time-wastiness. But you look at Jon McCurley, or Richard Feynman, or Monica Heisey, and you see people who have innate talent in more than one field and find time in the day or in life to nurture them. And above all who don’t get caught up on the social or cultural role of “I’m a performance artist, that means I can’t also be a comedian or be in a band” (Jon) or “I’m a Nobel-winning physicist, that means I can’t also be a good storyteller” (Feynman) or “I’m a prose writer, that means I can’t write for film or TV” (Monica). (Rick Moody’s ‘importance of play’.)

152. This leads to an important insight into what art is, and, though I think it’s applicable to all arts, I think it’s best approached from the poetry-prose question. People like to talk about “what’s the difference between a poem and a story?” The easiest answer of course is poetry is lineated and a short story is not lineated. But if you look at real examples of poems and real examples of short stories, you see that there tend to be other notable differences; poems tend to have less regular syntax; stories tend to move more by causality; etc.

153. However, it is not unusual for a poem to have one or many of the ‘short story’ tropes; neither is it unusual (though it is slightly less common) for a short story to have some of the poetry tropes. To wit (& obviously): some poems aren’t lineated and are still called poems; conversely, it’s pretty common for a “poem” to in fact be a conventional short story in every way except for the fact that it’s lineated. So “poem” and “short story” are more terms of marketing than of art, in the same way that the way a long narrative based loosely on the writer’s life is called a “novel” or a “memoir” or “a novel from life” (Heti) or “85% of a true story” (Klosterman) etc based on the aims of the marketers and/or how the writer wishes to think of themselves.

154. So the truth is that behind, or beneath, all the “named arts,” i.e. “poetry,” “short story,” “essay,” “memoir,” “autobiographical novel,” “mystery novel,” “thriller,” “high-wire circus production,” “musical,” “stage play,” “performance art,” “stand-up comedy,” “live music show,” etc, which are essentially labels so that audiences can understand what they’ll be getting, there is a much longer list of techniques and tropes, a sort of Platonic array not equal to any particular genre, available to be deployed by the artist to create each individual artwork, and which tend to get deployed more often in certain forms than in others.

155. For example, ‘the desires of two characters conflict’ is something that is deployed rarely in poetry, often in short stories, and almost always in stage plays and movies.

156. This is why it’s good to dabble: if you stay true to your primary artform, say fiction, you will come to focus on the primary characteristics of that artform—in this case plot, voice, characters, etc—without developing any of the secondary characteristics which nonetheless are still good to be practiced in, and which are primary to other forms, for example ‘the desires of two characters conflict’.

157. Dabbling also divorces trope from form in your mind, helpfully. If all you ever read were short stories and novels, you might think that narration is fiction. Reading poetry and watching movies with voice-over will help you see that narration is a technique in its own right. Do this enough and eventually you see that in fact “fiction” doesn’t exist at all; there are only individual artworks that deploy certain techniques and tropes, and the word “fiction,” seriously understood, is a marketing term, or, less-seriously understood, a convenient shorthand.

158. Of course the ‘convenient shorthand’ is very convenient. However, just as “race isn’t real” is true on one level, race is in fact real in people’s minds and is therefore useful to understand; likewise, because the categories of “fiction,” “poetry,” “play,” etc, are real in people’s minds, they are in fact real in that sense. However, just as the biologist and the farmer have different, equally legitimate, understandings of crops (the biologist’s being truth-based, the farmer’s being use-based; neither is ‘better’), it’s important for the artist to have a more nuanced understanding of art than the general public in order to be able to engineer art.

159. To return to Tolstoy’s ‘art comes from things we all do every day, practiced and paid attention to’ (in What is Art?)—storytelling, performing for each other, writing to each other, thrilling each other, lying to each other, tricking each other, making things for each other. The useful gestures get reused and become tropes.

160. Some artists hew close to the everyday-gestural bone, and that can feel ‘pure’. Life of a Craphead, early Cat Power, Shoplifting from American Apparel, Naoko Takahashi.

161. Other artists take preexisting tropes as their raw data, and that can feel genius in a different way; it thrills a different part of your brain. Infinite Jest, Charlie Kaufman, Dirty Projectors, Beyoncé’s Lemonade, Trecartin.

162. Probably every decent artist attempts to eschew all recognizable tropes, at first. You have this image of yourself as reinventing the wheel.

163. You find what works for you. However, you cannot choose what kind of (good) artist you will become. Be humble enough to share the gifts you actually have with the world (even if they don’t feel cool), be nimble enough to follow your genius, be open enough to dabble to discover it.

164. Different things are accomplished with machine language vs. Python with the same energy input from the programmer; one language is not ‘better’ than another. Do not valorize energy expenditure.

165. Be humble. Aim lower.

166. Embarking on a really big artistic project can be scary and stressful. Sometimes too much.

167. Every time you come back to any substantial project, you’re confronted with a really excellent reason it can’t move forward and the whole project is fucked. And every time you plow through it, and it’s fine. Until the next day, when you realize another extremely good reason it’s fucked. And the whole process starts over again, and you plow through the impossibilities. You have the ingenuity to conquer any problems.

168. It takes three days of working on the same project for your head to get fully into it. The first two days will often be immensely frustrating and will feel fake and on the third day you will be struggling to record all the project-related thoughts that are spilling out of you. Cf. Richard W. Hamming – “You and Your Research”:

If you are deeply immersed and committed to a topic, day after day after day, your subconscious has nothing to do but work on your problem. And so you wake up one morning, or on some afternoon, and there’s the answer. For those who don’t get committed to their current problem, the subconscious goofs off on other things and doesn’t produce the big result. So the way to manage yourself is that when you have a real important problem you don’t let anything else get the center of your attention – you keep your thoughts on the problem. Keep your subconscious starved so it has to work on your problem, so you can sleep peacefully and get the answer in the morning, free.

169. Looking at my green and blue binders with all my notes I didn’t end up using in the MetaFilter essay today (10/31/14), I realized that the bigger the success the bigger, also, the failure. The more ambitious it is, the more it will fall short of what was in your mind. So don’t be afraid of failure. Failure is a necessary ingredient of success.

170. Sentences get written while looking at the page; but stories get written while not looking at the page (while cleaning) (but having looked at the page that morning).

171. Say no. Say no more. Free yourself up. You don’t have to respond to every email or message you get. An empty day fills itself.

172. Like a page.