L10: Bootcamp

Hi,

I would like to say I have a simple goal, but it seems I’m pretty flexible in practice. I think of all the dabblers down through time, Da Vinci inventing the helicopter on the back of a piece of paper where he records an anecdote of himself filling up a room at a party with a room-sized balloon and laughing his ass off. Sure.

So in that spirit I’m going to tell you the story of how I went to coding bootcamp. It’s going to be kind of long. Here it is.

1. “Why not make $50 an hour?”

In 2012 I was in a relationship with a woman named Emma from Evanston, IL, on Chicago’s North Shore. This is a wealthy part of America and her family was wealthy. Her dad had gone to Harvard and made a lot of money on the stock market, then retired in his fifties. This is when I met him. At this point his main occupation was visiting every Major League Baseball stadium in the U.S., and living in his big beautiful house with a wraparound porch with his wife, visited frequently by his four adult children, who were all charming, troubled artists who seemed to be very fond of him, and who he doted on. In fact every night he sent out an email calculating the geographical mean center-point of everyone in the nuclear family. I remember thinking he was one of the happiest people I had ever met. I was at their house for passover in 2012, which lasted two fulls days, two full like 8-hour dinners, and to which about 20-25 friends and relatives were present, fluidly, coming and going, gefilte fish and apple sauce, and at one point he gave a toast. He said the secret to happiness was two things: one, “marrying well,” and two, not thirsting too desperately to be number one. “Being number two is good,” he said. “What’s wrong with number two?” I was at Emma’s wedding in 2019, in Evanston, and in a huge crowd of people he was crying with happiness.

I spent 10 days in that huge home at the beginning of the summer after my 2nd MFA year. Emma was despairing about her future, sort of moping around the house. Her dad took this as an opportunity to lecture her. One thing about Emma’s dad is that he used to say all the doors that had ever opened to him in his life had opened because of the name “Harvard.” Emma had been accepted to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, by far the most famous MFA program in the world, but had turned it down in favor of the University of Alabama, where we had met, because, she said, she liked the look of UA’s program better. Her dad, by this fact, was consternated. His whole life was testimony to the power of elite U.S. college brand recognition. But since Emma was now committed to studying the poetic arts at Bama, which would likely yield little profit, he thought she should learn a marketable skill. And since she’d have to work regardless, she may as well work for the highest amount per hour. This is where we join him, pacing his living room, gripping a can of PBR, his daughter half-hiding under the couch cushions: “Why not make $50 an hour, if you have to work 8 hours a day?” he said. “Learn to code, that’s a skill in demand. Why sit at a desk making $15 an hour when you could be making $50 an hour sitting at the same desk?”

When Emma and I broke up seven months later, I wrote a draft of a novel about our relationship in my $380/mo 1-bedroom apartment on 7th Street in Tuscaloosa, AL, while listening to Jessie Ware’s Devotion, on my desk that was a single sheet of 4’x8’ Home Depot plywood, and in this novel I had this recurring motif where people would offer other people life advice, and Emma’s dad’s harangue was one of them. I was basically mocking his simplistic logic—or, more generously, ‘ironizing’ it—in favor of the more pure life of the artist.

2. The Pure Life of the Artist

After I finished my MFA in spring 2014, I wanted to stay in the U.S. but couldn’t figure out how to do so, so I reluctantly moved back to Toronto, which was my default location. Once back in Toronto my main goal was always leaving it again, but in the meantime I initiated two income streams: 1) my friend and frequent editor Emily Keeler advised me to start writing for Hazlitt, and introduced me to an editor there, and I wrote a piece for them that took me all summer and made me $800; and 2), during that summer, I popped and served and swept up popcorn kernels at Cirque du Soleil on Cherry Street alongside 17-year-olds (I was 31) for $11/hour. Over the next year and a half, I spent most of my writing time on drafts of things I never published, mostly fiction, which =’d no money, and in the meantime, when Kurios: Cabinet of Curiosities ended its Toronto run, I got a job as a busser/food runner at a location of Pizzeria Libretto then just opening on University Avenue. Pizzeria Libretto serves delicious Neapolitan-style pizza and fancy cocktails and this particular location was about a block away from where all of Canada’s stockbrokers and bankers worked, and so a spigot of currency was open from their credit cards to our tip-outs. I got promoted to server and started making $200/night. While I was at Libretto, a friend posted about leaving a teaching job and looking for a replacement, to teach a couple 3-hour/week creative writing classes at George Brown College. It paid very little, but it seemed like a good opportunity, and I went for it, and got it, and that became a third income stream.

However, what I really wanted was to write, and in the spring of 2016 a few things happened: my first book, The Jokes, came out, and concurrently I landed 4 different freelance pieces. I thought, okay, my writing career is taking off, and I actually literally won’t be able to complete all these pieces by deadline if I’m working full-time at Libretto, so I quit Libretto. It was an intense decision and I still remember drawing up a long list of pros and cons. Libretto was the funnest job I ever had and easily the most highly paid.

This 4-freelance-pieces-landed-at-the-same-time thing turned out to be a fluke. I found freelancing super hard and was never as busy as that again, and was chronically low on money throughout 2016 and 2017. Part of my downfall as a freelancer was that I wanted to treat freelancing as a side hustle, when it demanded main-hustle attention. The other part was that journalism as an industry was, and is, dying.

It paid badly even when I landed pieces, is the thing. In 2017 I published the 5th-most-popular Hazlitt piece of the decade, which took me 18 months to write and not that much less research than you’d do for a masters degree, and I earned $1200. I started to tutor high school kids math to pay the rent. I was still, also, a creative writing “Professor” at George Brown College, from which I earned, in 2017, pre-tax, $11,087. Also, The Jokes had netted me $1200, negotiated up from $800. I’d worked on that for four years.

So this is why in October 2017, when my aunt Jeannie let me know the bachelor apartment on the 2nd floor of her house on Ward’s Island was empty, and was mine if I wanted it for a utility-bills-covering-only family rate of $200/month, I jumped at it.

3. “It’s A Comedy of Errors, You See”

I thought it would be fun to live, in Toronto-speak, “on the island,” with a hot plate and a futon—maybe be a good place to write. It was. Especially when I first arrived, it was all fall yellows and reds and ochres out the window. My view through a screen door was petite cottages wading in thick lake fog like seniors in the shallow end of a YMCA pool. There was some kind of yacht club about 20 feet from my aunt’s front door, and off-season sea vessels lay thick and white and upside-down on the brown grass like whales. To get to and from town, I’d take a 15-minute ferry, from which I’d take pictures of sunlight on waves, and then be disappointed at how few Instagram likes I got, as you do. I was very lucky to have this family favor, and I was also entirely outside of life and anything I wanted to be doing. Anyway, my aunt’s invitation was an in extremis kind of thing, not a permanent solution—she liked to have the space open for visiting guests.

I still had 3 jobs: writing prof, math tutor, & freelancer, plus unpaid novel-writer, but one additional project I’d started earlier in 2017 grew to fill up 2018: an idea I’d had for a web series about a woman having a bad time, which I’d brought to my then-roommate, Jade Blair. This was Miss Misery. MM would change the course of my life in wildly unpredictable ways.

Jade and I had been discussing the project since early 2017, but it started to feel real when I met my future lead, Aley Waterman, in the bar where she was working at the time, Burdock, on Apr 20. I was having a drink with Brad, mentioned in my last letter (L9). Aley thought (I learned later) Brad and I were a gay couple, “her new gay dinner party friends.” The three of us had a fun night. A few weeks later Jade and I were brainstorming possible MM leads in the conference room of the Toronto Writers’ Centre, and Aley’s face came to my mind. Aley and I met a few days later on a cold rainy afternoon. The café we were going to hit was closed, and we ducked into the run-down Coffee Time across the street (Bloor & Lansdowne, now gone, RIP). Via circuitous elliptical mumbling, I tried to explain my vision for this project I barely understood myself. Aley had no experience acting, but she was down. That winter, Aley’s then-roommate decided to move back to Vancouver, and on Feb 1, 2018, I moved from my island hotplate apartment into Aley’s 2-bedroom at Bloor and Ossington.

Work on MM kicked into gear. With Aley’s help, Jade and I wrote a million drafts of the scripts, hosted a live reading of them at Sandbox Media’s offices, shot a trailer, did an Indiegogo, and then started rehearsing and shooting in June 2018.

Aley had heard I was a character (“Paul”) in Catherine Fatima’s Sludge Utopia, which had just come out, and she read it, and a section of that book takes place in PAF, the art castle in France I often mention, and I said my friend Alex (also mentioned in L9) had been going there for years and telling me about it, and Aley got excited and said she wanted to go, and asked me to go with her, and I agreed, but reluctantly, because I didn’t think I could afford it financially or timewise.

But then on July 12, 2018, I found out the Canada Council of the Arts had awarded me $25,000 to write a novel. This amount of money, as you can see from the numbers I’ve been throwing around, was a big deal to me, like a life-changing amount of money. Suddenly the PAF trip seemed justified—appropriate, even.

Principal photography of Miss Misery wrapped on July 30. On July 31, Aley and I flew to France. I was grant-rich and feeling smart and guiltless, imagining this was exactly what I should be doing with art grant money.

For the purposes of this story, what’s important about what happened next is that:

In France I was really, really happy, and I realized that even if I couldn’t figure out how to live in the U.S., I didn’t necessarily have to live in Toronto. This obvious fact seems obvious on paper but somehow being in my mid-30s, with a hard-to-get creative writing college teaching job, moving somewhere else with no real plan just hadn’t seemed like an option.

However, almost immediately upon arrival, I realized my desire to leave Toronto outweighed my need for anything resembling a cogent plan, and I decided definitively that I wasn’t going back, that I wouldn’t return to teach at George Brown in the fall, and that I would move out of Aley’s place.

I then spent the next 2 years traveling and writing the book I’d told the CCA I would write, and gradually burning through first the CCA grant money, then my savings from the stockbrokers’ credit cards.

A fair amount of these 2 years of travel have been recorded in these letters themselves, and I know this is getting long, so I’ll jump directly to:

4. A long wooden dining room table in a quiet affluent Norwegian suburb, mid-day

As documented in previous letters, in 2020 I was in a relationship with a Norwegian woman in Norway. In June we were in deep lockdown in this beautiful house I was staying in for an unexpectedly long stretch. I felt like I was in this very safe and very unreal stasis. I was a guest in this home and wasn’t paying rent, but I was also only in Norway because COVID had relaxed visa restrictions. As soon as the pandemic lifted, I would have to go somewhere else, and I would need money. I had had a regular copywriting gig interviewing entrepreneurs and startup founders throughout 2019, but that had dried up the minute COVID hit. I had come to the end of a lifestyle.

I discussed this with Hanna. I don’t honestly recall if I’d ever mentioned anything tech-related before, or whether it was just something people said to each other in 2020, but Hanna said, “What about coding?”

We were sitting, as this section’s title suggests, at the long wooden dining room table in the suburb previously identified as Fornebu. Whatever hesitations I had about my relationship with Hanna, there was something, I think, about the mise-en-scène of the experience of cohabiting in a suburb of affluent young parents, with a dozen little kids playing in a miniature private jungle gym in the public square of these gorgeous stained-wood condos, in this nexus of neighborhood groups and building committees, that made me see it as something desirable, and possible, if only I could afford it.

It sounds dramatic, but something changed in me when Hanna said those words. I felt like I didn’t have to be a writer to be accepted. I felt I didn’t have to ‘produce’, artistically, to have access to people. I didn’t need ‘people’. I needed money.

5. “Who Makes Your Money?”

And that was it, really. I started experimenting with JavaScript and Python on Treehouse, data science on Udemy, did a little thing on datajournalism.com. I started following tech-adjacent people on Twitter. I read Antonio García Martínez’s Chaos Monkeys. I read some of the intensely annotated essays of internet eccentric Gwern Branwen. I read a bunch of blogposts and an eBook by Silicon Valley consultant Venkatesh Rao. I poked my head into the Instagram feed of Ryan Holiday (the Stoic Daily guy). I sniffed a novel about working at a startup in New York.

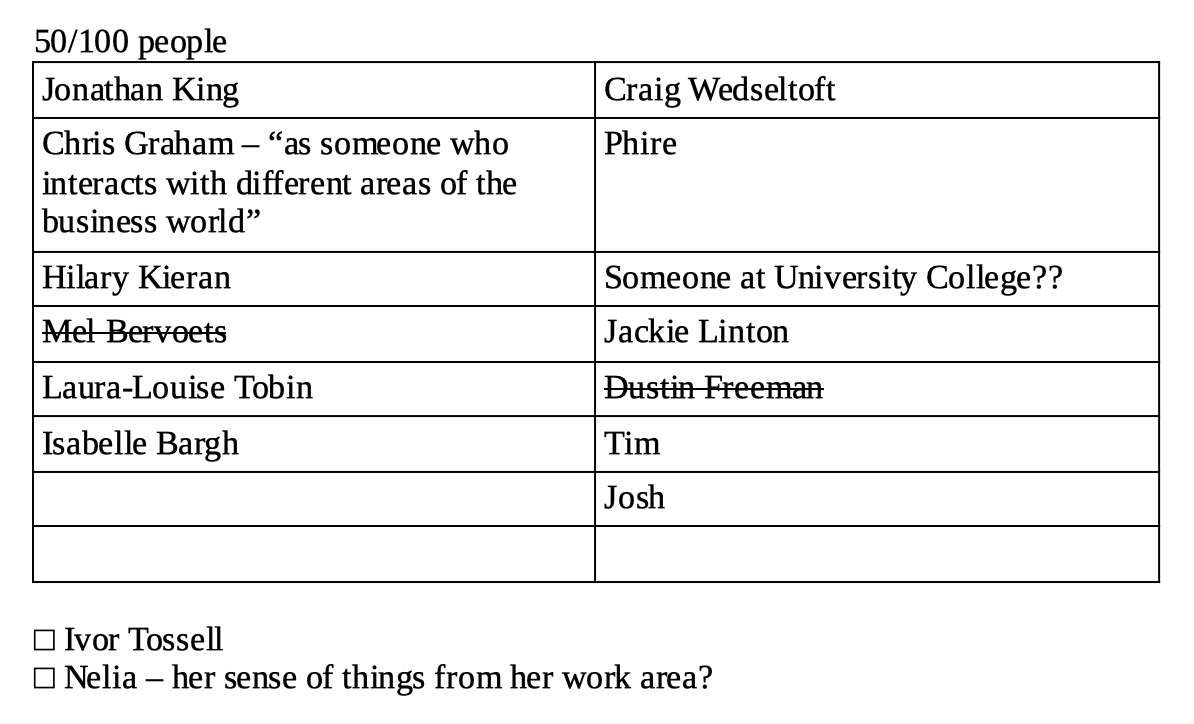

It was weird. I felt very unsure of everything. I had no idea which direction to go. Then I remembered a thing one of the entrepreneurs I’d interviewed in 2019 had done: “100 People in 100 Days,” © Keisha Mabry, which was basically Keisha talking to a bunch of people post-MBA, looking for opportunities. I made this list:

This was me brainstorming anyone I even vaguely knew who worked in tech or something tech-adjacent. I didn’t know anywhere close to 100 people, but I talked to most of the people above, and a few others. Eventually I homed in on Juno College and their frontend web dev immersive bootcamp.

I applied to that.

6. Apostasy

As soon as I even applied to bootcamp, I had this rush of relief for several days afterwards of finally, I’ve given up the stupid pipe dream of writing. I always felt strange that I actually ended up doing the thing I wanted to do when I was a kid, like—isn’t that a sign that critical thinking entered my decision-making process at absolutely no stage? I was living the life I conceptualized as an actual child, who thought “superb” was pronounced “super B” and denoted one notch less super than regular (“super A”). That kid, age like 8, was like “being a writer would be cool,” and for the next 29 years I never revisited that plan.

Weirdly, though, in the next few days, in the wake of being released from the stranglehold of ‘being a writer’, all these positive, optimistic feelings rushed in, about… writing. I felt freedom, terrible freedom, from the poisonous and all-consuming network of anxieties that had insinuated itself around my every capillary and axon since I first started hearing stories of my grandparents dining at Anaïs Nin’s house. I rarely talk about my (very tenuous!) family connection to some of the most famous writers of the 20th century, but I was made aware of it early, and it lodged itself in me pretty deep.

But in addition to feeling embedded in writing as like a world-historical movement, I also actually liked creating work, and now that I’d given up on professionalizing it, my writing-brain started to poke its little green worm head out of the sand, sensing the cessation of a decades-long anxiety storm, and was starting to look around at post-apocalyptic possibilities.

Because of course the thing is I love to write. I use it to knit together and make whole my life. As a rule I feel pretty lost, but sticking a bunch of facts about myself together in a fat paragraph is pacifying in a way few other things are. For one thing, it’s an effective corrective to catastrophic thinking, and creating a virtual self-portrait is about the best way I know to tease out self-deception, internal inconsistencies, and blind spots, to keep you honest and ethical, and to verify, to yourself if no one else, that you have lived. I started doing this obsessively at the beginning of losing my sister to a cult when I was 18. It has been helpful.

7. Bootcamp

Anyway, I learned I’d been accepted to Juno’s bootcamp on July 22, 2020. All my confusion rushed back in. I was nervous, terrified even, of losing myself. Nonetheless I moved to London, as mentioned in L9, on Sept 14, into my friend Tim’s spare room in his apartment beside Hampstead Heath. The next day, I started Juno’s 2-week intro web dev course.

The format was the same as the bootcamp itself, so I’ll explain it here: 8 hours a day of Zoom classes, 10am-6pm, Mon-Fri, Toronto time. Two or 3 charming, funny, generous instructors would be present on the Zoom call, plus about 30 students. At the same time there’d be a very active Slack chat popping off with questions and answers about whatever we were talking about, plus memes. It was fun. I’d usually spend about 3 additional hours a night coding, and then at least 8 hours a day on the weekends, completing the assignments due every Monday morning. Intense but fun.

Outside of class, I would hang out with Tim, and otherwise see one other person IRL ever: Hilary, an old friend from Toronto who is now also a web developer (listed in my “100 people” thing screenshotted above, in fact (last name spelled wrong)) who lives nearby. She would come over once a week and I’d make us lunch.

Tim, who splits his time between London and Montreal, went to Montreal on Oct 8. Then lockdown restrictions tightened, and Hilary and I stopped seeing each other in person. So then the only people I saw IRL were deliverers from Ocado, a grocery website, and Amazon, for 1-5 seconds, about once a week. I jogged several times a week, but I no longer jogged through the heath, because it was too crowded, so I jogged through the streets. Because Juno is based in Toronto, it worked best if my sleep schedule was more or less synced with Toronto time, so many of my jogs were on my lunch break, from 6-7pm (my time), or after class, post-11pm (my time). It was pitch dark outside during these timeslots, and often it was raining a little, or had just rained, or it started to rain mid-jog and I had to go back inside. This, I guess, is London for you.

The interpersonal deprivation at times had intense effects. Once, when I was waiting for my falafel from the white woman with dreads who stands a cart at the end of my street (which I went to like, twice), a newly pregnant woman explained to the falafel lady how despite lockdown measures she was thinking of visiting her grandma in Spain, because it might be the last time she’d see her alive, and she wanted her grandma to at least see her pregnant, even if she’d never meet the baby, and she also wanted to sit on the beach, but this one—and here she gestured to her male partner, seated beside her, who didn’t look up—doesn’t like the beach, so he doesn’t want to come. The falafel lady said it’s no crime to not like the beach, and maybe you could just visit your grandma on your own. And, standing there with my mask on pretending to read my phone, I thought, okay, these are the people I know now. This is my community now.

Hanna and I broke up on Oct 24 over the course of a sweet and civil three-hour Facebook video call, where we expressed gratitude to each other and agreed we both were in better places now than when we met, in part due to the other. Over the course of the next few weeks it would get sadder for both of us as the reality of the breakup sunk in. I was completely alone then. I got into the song “Not” by Big Thief and Phoebe Bridgers saying “I got everything I’ve wanted” and to some extent alcohol. I briefly dipped back into “I Gotta Find Peace of Mind – Live” by Lauryn Hill, which was my most-listened-to track of 2019. For a few days I really rabbit holed into online communities based mainly in California. Two of my uncles died, Joe and Ed. I allowed myself a short break from coding and went for a walk to a stationary store, where, bemasked, I bought 7 pens. On the walk home, in a cobblestone alley, I felt, or allowed myself to feel, the presence of my sister in me, in my head, her personality, her voice, her attitude, which is very proud, and exhorted me to walk upright and hold my shoulders back, and made me feel that I have nothing to be ashamed of, and I don’t need anything from anyone, that I’m not a desperate person, that I’m not constantly craving deliverance from my torment.

8. Completion

Tim came back on Nov 15. I turned 38 on Nov 26. The Juno crew gave me a warm Zoom welcome to class on my birthday; at least one balloon was involved. I spoke to Hanna for 10 minutes on a video call and cried my eyes out. Tim and I played three rounds of Hive. On Dec 18, bootcamp ended. I’d been alone for about 70% of it, and it was really nice to have the company of 30 people in a Zoom chat for 8 hours a day, not to mention a captive Slack audience for all the dumb jokes my brain compulsively generates.

Anyway, I know this is long. During a break from project #6, Detective Pokémon, my partners and I were swapping stories about how we ended up in the bootcamp. When I told a 45-second version of mine, one of my partners, Swetha, was like “you should write a book about that!” So, I thought maybe people would like to hear a somewhat extended version of all this, and now I have written it.

For now I’m going to skip over Christmas, on which I had a really exceptionally nice dinner here in London with my friends Monica and Stephen, and my job search, which was mercifully brief. I spent early January fixing up my portfolio and applying for jobs, and last Friday I was offered a job at Plogg, a company in Quebec, as a Junior Front-End Web Programmer. On Monday I went for a beautiful walk with Hilary, on a rare warm, clear sunny day, through the mud of the heath, and Friday was my first day as a professional coder.

As gestured at earlier, I do feel like I’ve defected from the hazy, polytheistic, but very real religion of literature, and have started to think about other ways I could contextualize myself. I’ve started to think about my actual roots, i.e., who my ancestors actually were and what they did. At one point I actually did kind of a major deep dive of the history of WASP culture—which might sound funny, but you follow the leads such as they are. What I realized is that my ancestry for at least the last century has been, essentially, rootless opportunist Anglophones hopping from one Western capital to another in search of love and money. Perhaps unsurprisingly, I have found this comforting.

It’s now Sunday afternoon. I have a fair amount of work to do to get up to speed at Plogg, so I’m probably going to spend the rest of this weekend doing that. In the next room, Tim is at his standing desk, watching his stonks.

Hope you’re well. If you’re getting this, I’d be interested in hearing from you, so write back if you feel like it.

Steve

Thanks for mapping this journey out, Steve. I think I'm approaching some version of this crossroads myself and so am grateful to read abt how someone I admire has traversed it, inside and out. And congrats on the new gig.